New Methods

What can transform a road into a place?

When designed and deployed correctly, and in the right context, crossing structures act as a new, visible layer of functioning landscape, weaving over and under our highways, in and out of the natural landscape. In this way, crossing structures can reveal and highlight the landscape and habitats our road networks have fragmented; they have the potential to express this remarkably—even beautifully.

Just as suspension bridges can be elegant and delicate in appearance but strong in function, wildlife crossings—whether overpasses or underpasses—can be beautiful in their simplicity while effective in linking habitats.

“If there’s beauty to an animal crossing, people’s eyes and minds tend to rest on it a bit longer and open to the meaning behind it.” —Jeremy Guth, trustee, Woodcock Foundation, and ARC founding sponsor

We believe crossing structures as solutions ought to be celebrated, visible and beautiful. But we know they must also be legible to function properly and to register with the animal clientele. This means that wildlife crossing structures must be specific to the species they are designed to protect, and for the context into which they are installed. In this way, crossing structures can become symbolic of place: their designs can signal we are in the landscape, each one slightly different in each context.

It’s also clear that people need to see the bridges (both overpasses and underpasses) to know they are there and that they work. When they see a crossing, people understand just how the chicken (or bear or deer) crossed the road successfully.

“We designed our crossing to look like it should have been there. We want people to see it and think, ‘How did we miss this?’” —Ted Zoli, bridge engineer and MacArthur Fellow

What’s different about building a bridge for wildlife?

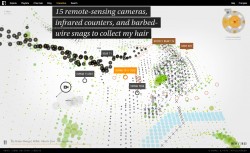

Wildlife crossing structures are really a new category of infrastructure. They require a collaborative, interdisciplinary systemic approach for effective planning and design. Single, iconic bridges will not accomplish much. To be effective at the most functional level, we need a network of crossings, just as highways are a network of roads.Highway engineering and transportation planning have traditionally been highly compartmentalized activities in which various experts work separately on distinct aspects of a project. Yet wildlife crossing infrastructure cannot be planned this way for the simple reason that there is more than one “client” for the project. Both humans and animals have different and sometimes competing needs related to any given crossing structure; some species prefer overpasses, while others prefer underpasses. All require safety.

But resolving such a design challenge requires more creativity and expertise than any one specialist affords. For this reason, wildlife infrastructure design is necessarily a collaborative craft, one that requires the input of many different types of experts, from ecologists to architects to landscape designers to engineers and transportation specialists. Road ecologists who study and understand animal interactions with highways must work proactively with the federal agencies and state departments of transportation that are responsible for engineering the roads to cleaning up roadkill.

“Some states have annual budgets in the tens of millions of dollars for cleaning up animal carcasses on the roads. But the people who do the cleanup and know the costs are not interacting with the planners and the engineers who design the roads where the accidents happen.” —Ted Zoli, bridge engineer and MacArthur Fellow

This type of proactive and creative collaboration has the potential to transform the ways in which human infrastructure and animal movement coexist. One day, perhaps crossings will become a defining feature of the American landscape experience.

![ARC [diagram]](https://arc-solutions.org/wp-content/themes/arc/images/arc-diagram.jpg)