New Solutions

What’s been done about roadkill, and why isn’t it enough?

New solutions to wildlife crossing infrastructure are intended to reduce the costs and to tailor each type of crossing to the specific species in various landscape contexts. We are also considering new solutions to the construction and material of these structures, as we may need to move, enlarge or downsize them based on changing wildlife movement patterns due to changes in habitats, climate or other factors. In the broadest sense, we aim to capitalize on the potential for crossing structures to tell a story—the story of our renewed relationship with wildlife and landscapes.

The time has come for new solutions in the evolving world of wildlife crossing structures. In general, new solutions should be:

- considered as early as possible in the transportation planning process so as to avoid the more costly problem of retrofitting or rebuilding;

- cost-effective in terms of materials, construction and maintenance;

- ecologically responsive to current and anticipated conditions;

- safe for humans and wildlife alike;

- flexible or modular for possible use in other locations;

- adaptive, to facilitate mobility of wildlife under dynamic ecosystem conditions;

- sustainable in terms of materials and energy use, and responsive to climate change;

- educational, revelatory and communicative to the public; and

- beautiful, engaging and remarkable.

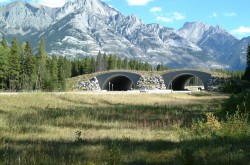

The ARC competition’s winning design is only one example of the innovation needed for new solutions for wildlife crossings. The HNTB+MVVA scheme uses ordinary materials and technology as well as construction techniques that are well established and, in particular, accessible in many locations across the continent. This has significant potential to reduce construction costs and improve construction accessibility. This solution combines emphases on wildlife habitat, behaviour and viability, with a practical intelligence and concern for long-term sustainability. The ARC jury noted in particular that this scheme “marries well a simple elegance with a brute force. It effectively recasts ordinary materials and methods of construction into a potentially transcendent work of design. In this regard it gives us confidence that it could be credibly imagined as a regional infrastructure across the inter‐mountain west” (ARC Jury Report).

“We could easily say today that wildlife crossings are no longer design or technical challenges. We have every capacity to implement these structures. What we really need is political, economic and social leadership.” —Charles Waldheim, chair of Landscape Architecture, Harvard University, and ARC jury chair

Wildlife crossings as living, learning laboratories

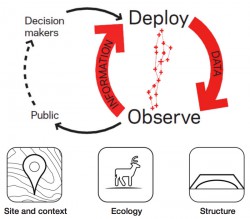

As more crossings are built, continuous learning through on-going monitoring is expected. Wildlife crossings are being designed as living experiments, complete with data-gathering technologies built into the structure. Wildlife crossings offer rich potential for learning: infrared cameras installed at crossing sites capture and record animals in transit; web cams transmit real-time wildlife movement data to science labs and classrooms alike; and hand-held applications bring the data to passengers in a passing car. From scientist to student to tourist, wildlife crossings reconnect us all to the landscapes that surround us.

In turn, the design of future crossing structures will improve. Based on the lessons learned from the monitoring data gathered, structural designs can and should be adapted to the site conditions and wildlife dynamics with each successive implementation. Over time, we can expect more radical and prototypical designs, along with other innovations in materiality, technology and ecological approaches. These new solutions will be welcome additions to what is already a promising new category of infrastructure.

“Imagine getting in the car at Thanksgiving to head home to where you grew up, and driving under a few wildlife overpasses. That should be part of the American experience.”—Ted Zoli, bridge engineer and MacArthur Fellow

Crossings concepts in the classroom

Despite its large scale, the park is currently in deteriorating ecological health and is poorly connected to adjacent ecologies and the surrounding urban fabric. A critical area of design exploration focused on the tenuous connection between High Park and the western waterfront territory along the park’s southern edge. Currently severed from its historic connection to the Lake Ontario waterfront by more than six layers of sprawling transportation infrastructure – including 1 major highway, 2 boulevards, 2 railway lines and a light rail street car line – the reconnection of High Park to the waterfront and the creation of a more holist park network along Toronto’s western beaches was a primary objective of the course.

The studio generated a series of new concepts for crossing structures, which can be viewed in the accompanying gallery or by clicking on the links below.

- Regeneration: It Takes a Village to Raise a Park

By David Burns

- DE-frag

By Megan Esopenko

- Trans-PLANTS: Giving and Receiving Landscapes

By Emilia Hurd

The ARC competition was “the most talked about design work of the year.”

Landscape Architecture Program, University of Toronto

![ARC [diagram]](https://arc-solutions.org/wp-content/themes/arc/images/arc-diagram.jpg)