News & Media

Wildlife Crossing Structures: An Innovative Global Conservation Strategy

A global movement to reconnect wildlife habitats and offer animals and drivers safe passage while traveling (or migrating!) has been gaining momentum for the past several decades. This article highlights some notable examples of how wildlife crossing structures have been used to mitigate the often devastating effects of highways and roads on migrating animals, while also making travel safer for people.

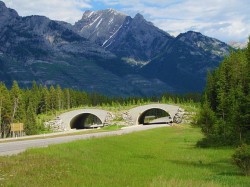

Perhaps the most famous of these structures occur in Banff National Park in Canada, along the Trans Canada Highway, where more than 20 vegetated overpasses and underpasses have helped ease the crossing of elk, deer, bears, wolves, moose and many other creatures.

In the Netherlands, more than 600 wildlife crossing structures have been built, including the world’s longest wildlife overpass, the Natuurbrug Zanderij Crailoo, which is 50 meters wide and over 800 meters long. It spans a business park, a river, a roadway, a railway line and a sports complex.

In Kenya, another notable wildlife crossing structure–an “ele” underpass– allows elephants to move between two wilderness areas and two distinct elephant populations separated by human development.

In the United States, Montana is the leader in wildlife crossing structures, with 41 structures serving everything from fish to large mammals. Wildlife crossing structures and systems are not just for large furry critters. Following the spring rains each year, residents of Amherst, Massachusetts, used to form ‘bucket brigades’ to ferry migrating salamanders safely across Henry Street, a two lane road separating the salamander population from its mating and spawning grounds. Yet in spite of the efforts to save them, many salamanders were killed by motorists, especially at night, when the migrations occurred and visibility was poor.

When word reached the British Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, they proposed a radical new solution. Teaming up with the University of Massachusetts, the Audubon Society, the ACO Polymer Company and local advocates, they constructed two tunnels underneath the road, allowing the salamanders to cross freely and without danger.

The tunnels were constructed according to the creatures’ natural habitat, with slats in the ceiling to help light and moisture penetrate. Specially designed fencing was also put in place to direct the salamanders toward the entrances of the tunnels, and at least 75 percent of the population used them to make the once perilous journey across the road.

The salamander tunnels in Massachusetts are just one of more than a thousand examples of wildlife crossing structures around the world.

Each day, over 1 million wild animals are struck and nearly killed on America’s 3.9 million miles of public roads. A study done by Congress estimated that these collisions cost us $8 billion dollars per year.

But the road system is responsible for other, possibly even more severe consequences to wildlife. Roads form barriers that separate animals from each other and from critical habitats (as was the case with the salamanders), potentially resulting in the disruption of gene flow and a decreased ability for species to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

We applaud the Colorado Department of Transportation and several Colorado counties for their efforts in building several wildlife crossings in Colorado. Now, it’s time for Colorado to reconnect the Rocky Mountain wilderness and build the proposed wildlife bridge over I-70 that claimed first prize in the ARC competition. The bridge would provide safe passage for many animals, including bears, bobcats, coyotes, deer, elk, big-horn sheep, lynx and other species, designating Colorado as a leader in conservation, while at the same time reducing the risk of costly and sometimes dangerous collisions for drivers.

Wildlife crossing structures are invaluable to many species like the endangered Florida panther, which, before the construction of several underpasses in the Everglades, needed to cross a number of dangerous highways to meet its 500 km spatial needs.

As the world population continues to grow and wilderness areas become increasingly scarce and fragmented, the presence of wildlife crossing structures may determine the fate of many species and prove critical to maintaining biodiversity across the globe. Nature Needs Half is an initiative to protect and interconnect 50 percent of natural lands and waters around the world. By ensuring habitat connectivity, wildlife crossing structures will improve the health of ecosystems and provide migrating animals access to critical environments, allowing them to thrive even in the presence of human development.

![ARC [diagram]](https://arc-solutions.org/wp-content/themes/arc/images/arc-diagram.jpg)